The Singrauli Coalfield, often called the heart of India’s thermal energy belt, is a major coal-producing region straddling the border of the Indian states of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. Over decades it has developed into a dense cluster of coal mines, captive and public-sector thermal power plants, heavy industries and associated infrastructures. This article describes the location, geology, types of coal, mining operations, economic and industrial significance, environmental and social challenges, and the future outlook for the region.

Geography and geological setting

The Singrauli Coalfield lies in the Son River valley and adjacent areas within the districts of Singrauli (Madhya Pradesh) and Sonbhadra (Uttar Pradesh). Often referred to as part of the larger Son–Valley coal-bearing belt, Singrauli occupies a landscape of rolling hills, plateaus and riverine plains at elevations ranging from about 250 to 650 meters above sea level.

Geology: The coal sequence in Singrauli belongs to the Gondwana group of formations — the ancient continental deposits that host the majority of India’s coal. Coal seams are generally part of the Permian–Carboniferous-aged coal measures (commonly referred to as Gondwana coals) and occur in multiple seam horizons. The strata are typically interbedded with sandstones, shales and mudstones, creating a layered geology suitable for large-scale surface mining.

Coal type and quality: Coal in Singrauli is predominantly non-coking and ranges from sub-bituminous to lower bituminous ranks. Characteristic features include:

- Calorific value: moderate compared to international high-grade coals — often in the range typical of Indian thermal coals (several thousand kcal/kg).

- Ash content: relatively high compared with many imported coals — this increases handling and combustion challenges at power plants and contributes to coal ash generation.

- Sulfur and moisture: sulfur content is generally low to moderate; moisture content can be significant in certain seams, affecting shipping and combustion efficiency.

Because of these geological and quality characteristics, Singrauli coal is primarily used in thermal power generation rather than in metallurgical (coking) processes.

Mining operations and infrastructure

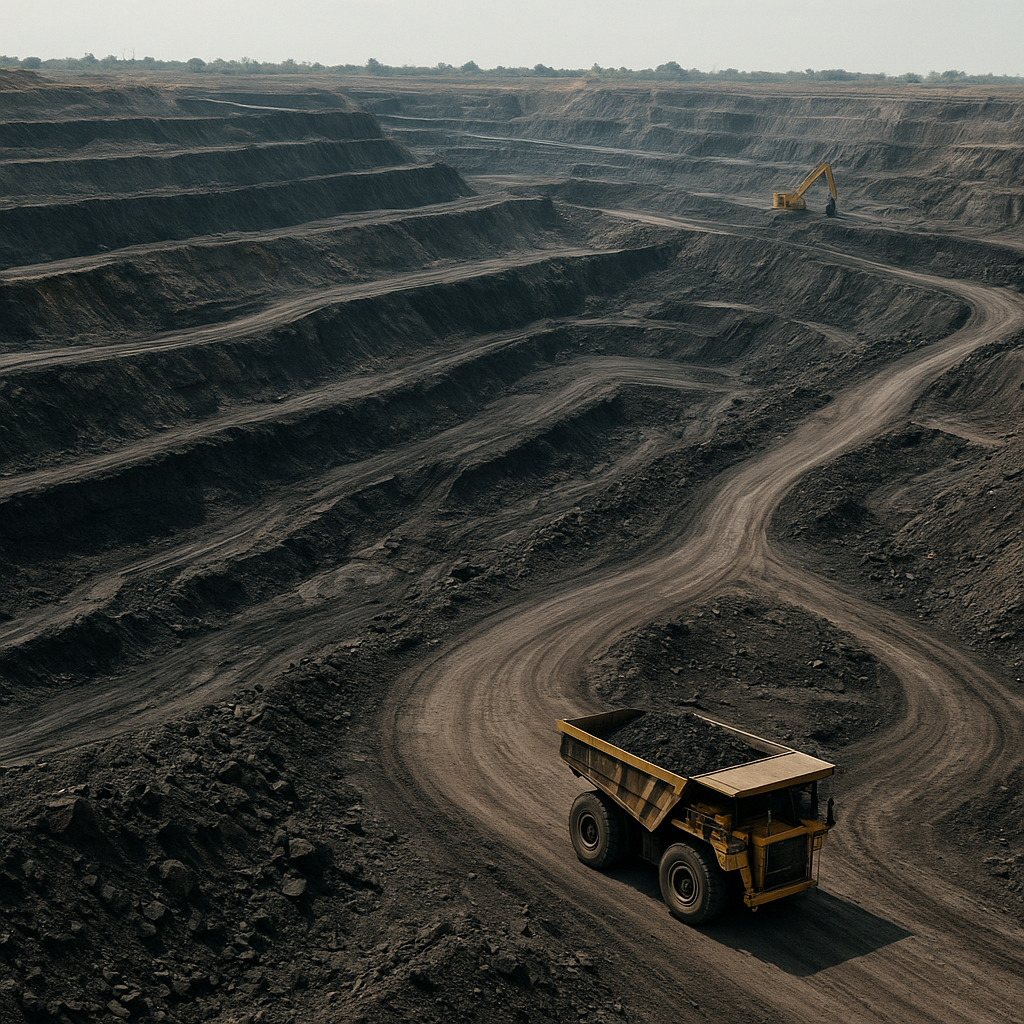

Singrauli’s mining landscape is dominated by large open-cast (surface) mines with high annual extraction rates. Over the past several decades, mining has expanded to create extensive pits and overburden dumps, connected by a network of haul roads, conveyor systems and rail links to power stations and industrial consumers.

Main operators and mine types

- Public-sector mining companies: Several Coal India Limited (CIL) subsidiaries and other state-owned entities have historically operated large mines in the belt, supplying both the public grid and captive plants.

- Captive mines: Many power stations and industrial units operating in Singrauli rely on captive mining blocks or long-term coal supply agreements to secure consistent fuel supplies.

- Mining methods: The predominant method is open-cast mining because of the shallow dip and wide lateral extent of the coal seams — this enables high-volume removal of overburden and coal with mechanized equipment (draglines, shovels, dumpers, and conveyors).

Transport and logistics

A dense logistics network supports the flow of coal from pit to plant. The Singrauli region benefits from:

- Rail connectivity that links mines to thermal power plants and major distribution corridors.

- Conveyor belts and dedicated overland conveyors used for short-haul delivery to nearby power stations.

- Road transport for ancillary movement, though heavy reliance on rail and conveyors helps lower per-unit transport costs for high tonnages.

Associated industrial infrastructure

Around the coalfield, extensive ancillary infrastructure has emerged: large thermal power plants, coal washeries, ash-handling facilities, residential townships for workers, hospitals, and educational institutions. The clustering of these facilities has created an industrial ecosystem that is both an economic engine and a set of environmental stressors.

Economic and industrial significance

Singrauli has gained national prominence for its strategic role in India’s electricity generation and heavy industry supply chains.

Power generation hub

The region hosts a concentration of major thermal power plants owned by central and state utilities as well as private companies. These plants, often sited close to coal mines to minimize transport costs, collectively account for a significant portion of India’s thermal capacity. Among these, one of the largest installations located in the broader Singrauli–Sonbhadra region is the NTPC Vindhyachal complex (a flagship unit for NTPC) with an installed capacity that makes it one of India’s largest thermal power facilities.

Contribution to energy security

By supplying coal to nearby plants and through long-term contracts to grid-connected stations, the Singrauli Coalfield contributes to regional and national energy security. Domestic coal from Singrauli helps reduce dependence on seaborne coal imports for power generation in central and northern grid regions.

Employment and local economy

Coal mining and related industries are major employers in the area. Direct employment is provided by mines, power plants and support services, while indirect employment emerges from transportation, hospitality, trade and small-scale manufacturing. The economic multiplier effect of mines and power plants supports local markets and townships, often transforming small rural settlements into industrial towns.

Revenue and fiscal impact

Revenue generated through coal production, royalty payments, corporate taxes and electricity generation contributes to state and central government finances. Local administrations receive funds that are nominally earmarked for infrastructure, welfare schemes and rehabilitation — though disbursal and effectiveness vary across programs and time.

Statistical snapshot and figures

Precise, up-to-the-minute numbers for reserves and annual production can change as new assessments and mining output cycles occur. However, some consistent themes and figures characterize the Singrauli Coalfield:

- Reserve base: The coalfield is among India’s significant coal-bearing areas with hundreds to thousands of millions of tonnes in in-situ reserves across multiple blocks. These reserves underpin multi-decade mining plans for large operators and captive users.

- Annual production: The region’s annual production over recent decades has been in the range of many tens of millions of tonnes, supporting multiple large thermal units. Production varies year-by-year depending on demand, mine expansion, regulatory clearances and operational constraints.

- Power capacity served: The coalfield supplies fuel to power stations whose combined installed capacity in the broader cluster exceeds several thousand megawatts — cumulatively contributing to a major share of regional thermal capacity.

Because statutory reports and company disclosures periodically update figures, readers seeking exact current numbers (reserves in million tonnes, annual production in MT, and installed capacity in MW) should consult the latest annual reports of Coal India Limited, NTPC, and the Ministry of Coal / Ministry of Power for authoritative statistics.

Environmental and social impacts

While Singrauli’s role in India’s energy landscape is pivotal, the environmental and social consequences of intensive mining and thermal power generation are substantial and multifaceted.

Air quality and emissions

Open-cast mining and coal combustion generate dust and particulate emissions. Thermal plants release flue gases containing CO2, NOx and trace pollutants; coal ash storage and fly ash handling lead to fugitive dust and potential contamination. These emissions adversely affect local air quality and can have public health implications for nearby communities.

Water resources and hydrology

Mining and power plant operations are water-intensive. Groundwater extraction for coal seam dewatering, dust suppression, and thermal plant cooling can lower water tables and stress local wells. Surface water bodies can be impacted by runoff carrying suspended solids and by effluents from industrial processes if not properly treated.

Land use, deforestation and biodiversity

Large open-cast mines require clearing of vegetation and conversion of land from agricultural or forest use to industrial landscapes. Habitat fragmentation and loss of biodiversity are documented concerns, especially where mines encroach on forested tracts or wildlife corridors.

Displacement and social disruption

Large-scale mining often requires land acquisition and resettlement of local communities, including tribal populations. Resettlement and rehabilitation policies have evolved over time, but implementation challenges remain: livelihoods, cultural dislocation, adequacy of compensation, and quality of resettlement housing are recurring community concerns.

Waste management and ash disposal

High ash content in coal means that thermal plants in the Singrauli belt produce large volumes of coal ash. Managing ash ponds and utilizing fly ash in construction materials are important mitigation strategies. Without proper safeguards, ash pond breaches and seepage can contaminate soil and water.

Mitigation, regulation and corporate responsibility

Recognizing the environmental footprint, regulators and companies have pursued mitigation measures and corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs. Key efforts include:

- Strict compliance with environmental impact assessments (EIA) and environmental clearances for new mines and plant expansions.

- Installation of pollution control technologies: electrostatic precipitators, flue-gas desulfurization where applicable, and dust suppression systems in mines.

- Progressive mine reclamation and afforestation programs to restore landscape and stabilize dumps.

- Water treatment facilities and ash utilization initiatives to reduce ponding and contamination.

- CSR projects in local communities focusing on healthcare, education, vocational training, drinking water supply and livelihood restoration.

Nevertheless, the pace and scale of mitigation do not always match the rapid expansion of mining and industrial activity, leading to ongoing debate between stakeholders, environmental groups and policy makers.

Interesting facts and regional highlights

- Energy cluster nickname: Singrauli has often been called an energy capital or energy corridor because of the concentration of coal-based power generation in a relatively small geographic area.

- Strategic location: The coalfield’s proximity to central and northern load centers reduces transport costs compared with sourcing from distant mines or imports.

- Integrated industrial ecosystem: Power plants, captive mines, coal washeries and heavy industries form interdependent supply chains that support large-scale industrial activity across the region.

- Rehabilitation experiments: Several mined-out areas have been targeted for reclamation, afforestation and conversion into community assets, though success varies with long-term stewardship.

Future prospects and challenges

The future of the Singrauli Coalfield will be shaped by a combination of market forces, environmental policies, technological change and energy transition trends.

Demand and supply dynamics

India’s continued growth in electricity demand will maintain a baseline requirement for domestic coal in the near to medium term, especially for grid stability and base-load generation. Singrauli’s proximity to large demand centers and existing infrastructure suggests it will remain strategically important.

Cleaner coal technologies

Adoption of more efficient thermal cycles, supercritical and ultra-supercritical boilers, and emission control systems can reduce specific emissions per unit of electricity generated. Investment in such technologies at Singrauli’s plants would improve thermal efficiency and lower environmental impacts.

Transition and diversification

As India pursues ambitious renewable energy targets, the long-term role of coal is likely to evolve. For Singrauli, diversification into ancillary industries, development of clean-coal demonstration projects, and economic transition programs for affected workers and communities will be central policy questions.

Policy and community engagement

Stronger, transparent frameworks for land acquisition, resettlement, environmental monitoring and benefit-sharing with affected communities will be critical to maintain social license for mining operations. Public participation, third-party audits and robust grievance redressal mechanisms are essential for sustainable outcomes.

Conclusion

Singrauli Coalfield remains one of India’s most significant coal regions, supplying fuel to an extensive cluster of thermal power plants and supporting a dense industrial ecosystem. Its geological endowment and strategic location have driven decades of mining and industrial development, generating employment, revenue and energy security benefits. At the same time, substantial environmental and social costs call for careful management, improved technology adoption, and responsive governance. The coming decades will test how Singrauli adapts to India’s evolving energy landscape — balancing the needs for reliable electricity, economic development and ecological stewardship.

Key terms: Singrauli, coalfield, Gondwana, sub-bituminous, coal, open-cast mining, thermal power plants, NTPC Vindhyachal, reserves, environmental impact